|

|

|

On the Life and Mathematics of K. Itô and W. Döblin

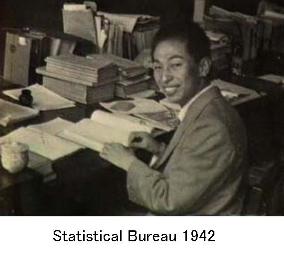

Kiyosi Itô was born on September 7, 1915, in Mie prefecture, Japan. His father was a high school teacher on Japanese and Chinese literature. Kiyosi Itô passed away on November 10, 2008, at the age of 93. He entered Tokyo University, Department of Mathematics, in 1935 and graduated from it in 1938. After graduation, he worked in the Statistical Bureau of the Government in Tokyo until he became an Associate Professor at Nagoya University in 1943. During this period, he was also awarded a research grant of the government, and thanks to the kindness of the head of the Bureau, he was able to spend enough time on his research in the Department of Mathematics at Tokyo University.

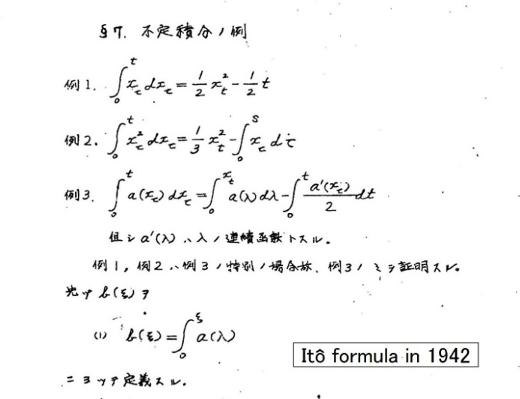

In 1942, Itô published his first two papers [I1, I2]. The first one [I1]

presented what is nowadays called the Lévy-Itô decomposition of a Lévy process.

The second one [I2] was in a mimeographed handwritten Japanese journal issued

from Osaka University and contained already the stochastic integral, stochastic

differential equations with Lipschitz coefficients and Itô's formula. It is

still hard for me to imagine how such big results could be attained in such a

short period of time starting from almost nothing.

In a film, K. Itô explains how he started to work in probability theory: “In

1935 I visited with my classmates Kodaira and Kawata a bookstore, a foreign book

dealer in Tokyo, and encountered Kolmogorov’s book [K1]. Kodaira told me that

this is said to be Probability Theory. Of course, I knew what the word

“Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung” meant. But I did not take it seriously at that

time. After 1937, I got gradually interested in Probability Theory and realized

that this book by Kolmogorov is what I had been truly looking for. Since then, I

have kept it as the firm cornerstone in my mathematical thinking while advancing

ahead. From my high school days, I was very fond of mathematical descriptions in

mechanics. I preferred Mathematics to Physics as it is more rigorous, but I was

also concerned with the practical use of mathematics.

In the mathematical community of Japan, Probability Theory was not recognized as

an independent branch of mathematics. I strongly felt that Probability Theory

should be of its own interest and of its own significance as a new field in

science, not just something subordinate to other branches of mathematics like

Fourier Analysis, Differential Equations, etc.

When I came across the book of P. Lévy [L] where the processes of independent

increments were studied on the sample path level and the Lévy-Khintchine formula

was then derived by taking an

expectation, I was extremely impressed. I keenly realized that Probability

Theory must be developed in this way. But, for P. Lévy, compound Poisson

processes were well-known objects that had arisen in practical problems of

insurance and he might have reached a general Lévy process quite constructively

as their possible limit without big surprise. I then made the presentation in

[L] more rigorous with a help of the idea in [D] on the concept of the regular

(càdlàg) version of the sample path.

With this experience, I turned to a construction of a Markov process

interpreting Kolmogorov's analytic approach in [K2] in the following way: the

sample path ![]() of a

Markov process (in the diffusion case) is a continuous curve possessing as its

tangent at each time instant t the infinitesimal Gaussian process

of a

Markov process (in the diffusion case) is a continuous curve possessing as its

tangent at each time instant t the infinitesimal Gaussian process

![]()

I spent almost one year by repeatedly drawing pictures of such curves before

arriving at a right formulation of stochastic differential equations.

My first daughter was 2 years old, and I remember that she said “Daddy is always

drawing pictures of kites!” However, such a drawing convinced myself that a

general coefficient of the equation ought to be a functional of the whole past

of events

![]() , a process

adapted to a filtration

, a process

adapted to a filtration

![]() in the modern term,

and that it is really an infinite dimensional and non-linear object.”

in the modern term,

and that it is really an infinite dimensional and non-linear object.”

A few years after the end of the Second World War, Itô sent J.L. Doob a

manuscript of an extended English version of his 1942 Japanese paper asking for

a possible publication in the USA. No Japanese journal at that time allowed such

a long paper due to the shortage of paper. Doob immediately appreciated its

significance and kindly arranged its publication in [I3].

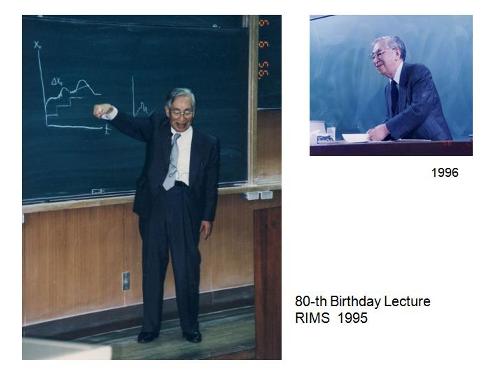

Itô became a Professor of Kyoto University in 1952. He was also a Professor of

Stanford University (1961-1964), Aarhus University (1966-1969) and Cornell

University (1969-1975), respectively. During these periods of being abroad, Itô

occasionally came back to Kyoto and gave very influential lectures on branching

processes, point processes of excursions and so on. He retired from Kyoto

University in 1979. He was then a Professor of Gakushuin University, Tokyo,

until 1985.

From 1954 to 1956, Itô was a Fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study at

Princeton University, where W. Feller had started his investigation of the one

dimensional diffusion processes.

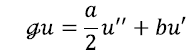

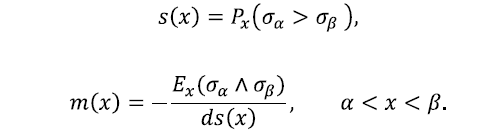

He tells the following about this period: “When I was in Princeton, Feller

calculated repeatedly for a one dimensional diffusion with a simple generator

the quantities like

In the beginning, I wondered why he was repeating so simple computations

as exercises. However, in this way, he was bringing out intrinsic topological

invariants that do not depend on the differential structure. I understood that

the one dimensional diffusion is a topological concept but I was not as

thoroughgoing as Feller.

When Feller told me about this, he said he once listened to a lecture by Hilbert

who mentioned “Study a very simple case very profoundly, then you will truly

understand a general case.’’ I like to convey these words by Hilbert to you.”

Masatoshi Fukushima, Toyonaka Osaka

References

[D] J.L. Doob (1937), Stochastic processes depending on a continuous

parameter, Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 42, pp. 107-140.

[I1] K. Itô (1942), On stochastic processes (infinitely divisible laws of

probability) (Ph.D. Thesis), Japan. Journ. Math. 18, pp. 261-301.

[I2] K. Itô (1942), Differential equations determining a Markoff process (in

Japanese), Journ. Pan-Japan Math. Coll. 1077 (English translation

in Kiyosi Itô Selected Papers, pp. 42-75, Springer, 1986)

[I3] K. Itô (1951), On stochastic differential equations, Mem. Amer. Math.

Soc. 4, pp. 1-51.

[K1] A. Kolmogorov (1933), Grundbegriffe der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung,

Springer, Berlin.

[K2] A. Kolmogorov (1931), Über die analytischen Methoden in der

Wahrscheilichkeitsrechnung, Math. Ann. 104, pp. 415-458

[L] P. Lévy (1937), Théorie de l'Addition des Variables Aléatoires,

Gauthier-Villars, Paris.

Kiyosi Itô was born on September 7, 1915, in Hokuseicho, Mie prefecture,

Japan. He died last year on November 10, 2008, in Kyoto, at the age of 93.

Between these two dates lies an extremely successful career: in particular, the

creation of modern stochastic analysis with the central notion of the stochastic

integral in his paper from 1942, “On stochastic processes”, that provides a

probabilistic underpinning of Kolmogorov's analytical approach to diffusion

theory. Without these fundamental concepts, many areas of the theory of

stochastic processes that are the subject of this conference are unimaginable.

For his outstanding work, Itô received numerous prizes, and many honorary

doctorates. He was elected to the Academies of Sciences in Japan, the US and

France. Post-war Germany had no National Academy until recently. From our

perspective, Itô's work was honored by the Gauss prize

sponsored by IMU and DMV. And Itô received the renowned Israeli Wolf prize.

Only about half a year before Itô, on March 17, 1915, Wolfgang Döblin, second

son of the German-Jewish novelist Alfred Döblin, was born in Berlin. His family

emigrated to Paris in 1933 and Wolfgang became French. He studied mathematics at

the Sorbonne, did a doctorate with M. Fréchet in probability, was drafted for

the French army in 1938. When German troops were advancing in Eastern France in

summer 1940, his military unit in disarray, he took his life on June 21, 1940,

in a barn in Housseras, at the age of 25. In the last two of these 25 years,

during his military service, and in the period following the German attack on

Poland, known in France as la drôle de guerre, he had worked on a

manuscript which he decided to send as a sealed envelope (pli cacheté) to

the archive of the Académie des Sciences in Paris. He was never able to withdraw

the envelope himself, so his manuscript was shut away in the archive for 60

years, and made accessible only in 2000 after his brother Claude had given his

consent.

Though Itô and Döblin were born almost at the same time, it is hard to imagine

two more contrasting careers. If it comes to their mathematical goals, however,

surprising similarities appear. This is already indicated in the title of

Döblin's pli cacheté manuscript Sur l'équation de Kolmogoroff.

Roughly, as Bernard Bru and Marc Yor found out after it was opened in 2000 in

Paris, in the school pupils' exercise book in which Döblin had scribbled his

notes, were hidden elements of a weak form of Itô's stochastic approach to

Kolmogorov's parabolic PDE.

I cannot and do not want to be more specific on the relationship of the

mathematical work of Itô and Döblin at this point, and also not reveal more

about the tragic background story. To continue elaborating on this from the

mathematical perspective, I am glad and proud to present to you two outstanding

mathematicians, who have worked in the footsteps of both Itô and Döblin,

Masatoshi Fukushima from Osaka and Hans Föllmer from Berlin.

Masatoshi Fukushima received his Ph.D. with Kiyosi Itô as advisor. He is

globally known and renowned for his pioneering work at the interface of

stochastic processes and analysis, the mathematical field starting at

Kolmogorov's and Itô's approaches to the heat diffusion, with a modern focus on

Dirichlet forms. He will now talk about his impressions of the life and legacy

of his teacher Kiyosi Itô.

I am now very proud to announce my colleague Hans Föllmer. Hans is a globally

recognized pioneer in the area of stochastic analysis and finance. On the first

sight a different area, his work witnesses the striking efficiency of

mathematical concepts. Namely, Itô's and Döblin's work, starting in paradigms of

physics, can nowadays also be seen as fundamental for mathematical finance. Hans

will talk about Döblin's work and the link to Itô's.

We now return to the tragic background of Wolfgang Döblin's short career. I must

confess that during my years of study of Mathematics and Physics at the

University of Munich when I heard, in my first course on Markov processes, about

the famous Döblin coupling technique, I thought that the novel “Berlin

Alexanderplatz” had just been written by a multi-talent in literature and

mathematics. Only after 2000, French friends told me about the pli cacheté

and the tragic story of the writer Alfred's mathematician son Wolfgang. The

story left me dumbfounded when I first heard of it.

Probably the same happened to two journalists from Hamburg and Amsterdam, Agnes

Handwerk and Harrie Willems, who are both present in this room, and who got

seized by the extraordinary story. They first met with Bernard Bru, professor at

the university Paris 5. He reported about how in 1991 at the Acadèmie des

Sciences in Paris he came to know of the existence of a sealed envelope, while

preparing a meeting in the US in memory of Wolfgang Döblin, organized by Kai-Lai

Chung and Joe Doob. Bernard Bru encouraged the journalists to work on a

documentary about the story. They produced a radio presentation, followed by a

video film. It is this video film, also available as a DVD from Springer that we

will now present to you. Please enjoy it.

Peter Imkeller, Berlin

Further information about the conference event on Tuesday

featuring K. Itô and W. Döblin and the tragic story about the sealed envelope

can be found in

[1] M. Fukushima: On the works of Kiyosi Itô and stochastic analysis.

Japanese Journal of Mathematics 2 (2007), 45-53

[2] B. Bru, M. Yor: Comments on the life and mathematical legacy of Wolfgang

Doeblin, Finance and Stochastics 6 (2002), pp. 3-47.

[3] P. Imkeller, S. Roelly: Die Wiederentdeckung eines Mathematikers: Wolfgang

Döblin, Mitteilungen der Deutschen Mathematikervereinigung 15

(2007), pp. 154 - 159, ISSN 0947-4471.

[4] Rediscovered Proof: Wolfgang Döblin. IMS Bulletin 38 (3), pp.

8-9.

[5] Handwerk, H. Willems: Wolfgang Doeblin A Mathematician Rediscovered, DVD,

PAL, (English, French and German), Springer, Berlin 2007, ISBN

978-3-540-71959-5.